The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley is now out in France. Published by Éditions Gallimard and translated by Mona de Pracontal. I am very grateful.

Archive: Author: Hannah

Les Douze Balles dans

New York Times Reviews 12 Lives

A Heroine Comes of Age With Her Pistol-Packing Father

Review by Pete Hamill

New York Times, April 11, 2017

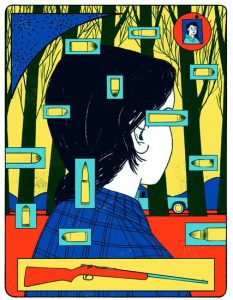

The engine powering Hannah Tinti’s complex new novel, “The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley,” is presented in the very first sentence: “When Loo was 12 years old her father taught her how to shoot a gun.” Bang, bang. Guns are normal in the Hawley household, where Loo (short for Louise) and her father, Samuel, live together. He keeps an assortment of firearms in his room, in closets, in boxes and in duffel bags. He often cleans them at the kitchen table, with the caressing attention of a priest. His daughter is not allowed to touch them. But they are there, and she watches intensely to learn “what she could about their secrets.”

Christina Daura

He leads her into the nearby woods with her grandfather’s rifle hanging across his shoulders. He is in his 40s now, tall and lean, looking younger than his age. When they are alone in a clearing, he gives her a first lesson in shooting. The target is a tree in the woods. Hawley talks her through the moves, including the release of a half-breath just before shooting. She sets herself, aims, then pulls the trigger.

And misses.

“Everyone misses,” Hawley tells her, scratching his nose. “Your mother missed.”

“She did?”

“The first time,” he says. “Now slide the bolt.”

Loo’s mother, Lily, died accidentally in a lake in distant Wisconsin before the young Loo could truly remember her. That loss provides an emotional anchor for Tinti’s story — and also for Loo herself, who still disappears at least once a day into the bathroom where Hawley has created an improvised shrine to his dead wife. As father and daughter moved around the unfamiliar American countryside, often abruptly, he always took the elements of the shrine with him to the next place. Photographs, a grocery list, the scrawled remnants of a dream. Like visible fragments of memory. The shrine and the guns establish a sense of home, a sense of continuity as Loo grows up. She may not recover her mother, but eventually she will master the holy art of shooting.

The story is bound together by memory as a kind of highlight film. Which is to say, by memory as it actually is and not as a neat, banal narrative or a huge baroque melodrama. Loo’s memories, and her father’s, are often triggered by subtle moments: a snatch of song, the rumble of fireworks, the aroma of food, sudden ripples of offstage laughter. And yes, pictures in a cramped bathroom. Sometimes the sun gleams in those images. But more often they are streaked by deep, threatening shadows. In this portrait, those shadows also obscure the true nature of Samuel Hawley.

The reason: Hawley is an outlaw. Not a gangster, because he retains no membership in a gang. Hawley is a freelancer, using his skill with guns to enforce criminal assignments: picking up certain very valuable cargo, usually in states where he does not live, and delivering it for a fee to the master planners. He steals cars to get around. He does what is necessary to survive his assignment. Hurting strangers. Killing, if that is necessary. He has a few freelance criminal friends, loners shaped by jails and violence. They often work together. In civilian life, Hawley poses as a fisherman or a house painter. He carefully hides his true identity from his daughter.

But he also pays a price. The 12 lives of the novel’s title are represented by 12 bullet wounds in his body, a kind of stations-of-the-cross marker for the scars Hawley has suffered in the living of his shadow life. His body has been punctured by too many bullets, along with the interior wound of losing his wife, and his great fear of harm coming to his daughter. Hawley’s love for Loo is tender and pure, a reprieve from an otherwise sinful existence. It makes Hawley an admirable father, and the novel more than a case for the humanity of gun nuts.

As his own story moves on, Hawley begins to self-medicate against physical pain or mental agony. He teaches his daughter to roll cigarettes for him. And he chooses alcohol as his own most useful medicine. The alcoholic blur pushes away the sharp edges in his mind. It doesn’t matter where father and daughter are. San Francisco. Oklahoma. Massachusetts. What matters is to sleep at night. And for Loo to go to a regular school and make friends. And so they do, in Olympus as in their other homes. But when Hawley digs for clams at the shore, he always has his back to the sea while he watches the people.

The story has a few other important characters. One is Loo’s maternal grandmother, Mabel Ridge, who is severe and wintry, as if convinced that Hawley and Loo are responsible for Lily’s death. There’s an insecure boy named Marshall Hicks, who once got fresh with Loo. Her response: She broke one of his fingers. Later, they fall in love. When Hawley is away, Marshall comes to sleep with Loo. Now they are seeing each other more clearly, as evoked by Tinti’s keen eye:

“Marshall sat up and looked around Loo’s room, his eyes resting on each piece of furniture and item on her bureau. A bowl of shells, a strip of Skee-Ball tickets from the county fair, a pile of comic books, novels and astronomy guides, some half-melted candles from a power outage, a wad of balled-up tissues from her last cold, a small batch of cormorant feathers that she’d found and kept, because she liked their iridescent black color. Loo watched him puzzle over each object. It was as if he was measuring her life.”

There are surprises too. And diversions. And mysteries. There is an extended scene with Hawley’s long absent father, who vanishes again when it ends: A vision? A delusion? We don’t know, but we read on, carried by Tinti’s seductive prose. She has a deep feeling for the passage of time and its effect on character. And when it’s appropriate, she can use her vivid language to express the ripping depth of human pain.

As this strikingly symphonic novel enters its last movement, the final bars remind us that of all the painful wounds that humans can endure, the worst are self-inflicted. The evidence is there in the scar tissue that pebbles the body of Samuel Hawley, and there too in the less visible scars on his heart.

Pete Hamill has written for New York newspapers and magazines since 1960 and has published 22 books, including the novels “Snow in August” and “Forever.” He is a writer in residence at the Carter Journalism Institute at New York University.

NPR’s Weekend Edition

Click below for audio.

Washington Post Review

A thriller with heart:

Hannah Tinti’s ‘The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley’

by Ron Charles

If only I’d had a copy of Hannah Tinti’s terrific new novel, “The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley.” This is the ancient myth of Hercules — the plot of all plots — re-engineered into a modern-day wonder. Tinti, the editor and co-founder of One Story magazine, knows how to cast the old campfire spell. I was so desperate to find out what happened to these characters that I had to keep bargaining with myself to stop from jumping ahead to the end. (Matt Reeves, lined up to direct the next Batman movie, has already optioned the novel for television.)

The story unfolds in Olympus, but not the celestial realm of Zeus and his family. This is Olympus, Mass., a small fishing town, which is typical of the radical transformations Tinti makes to her source material. Having grown up in Salem, she understands the flinty personalities of New England, that baffling tension between self-reliance and community spirit.

Samuel Hawley is a widower who has just moved into town with his 12-year-old daughter, Loo. He’s ruggedly handsome enough to turn heads but gruff enough to keep people at a distance — a conflicted, compromised hero whose lineage stretches all the way from the Old West to the old gods. Loo, meanwhile, is a precocious girl who “had grown strange,” Tinti writes, “the way children will when set apart.” Although Olympus is where Loo’s late mother once lived, the town regards these new neighbors with suspicion. Loo is cruelly teased at school until she beats a few of her tormentors to a bloody pulp. Her father objects only because she got caught.

On one level, this is the tender story of a girl trying to carve out a usable identity for herself while maturing in the shade of her father’s endless grief. Loving as he is, devoted as he is, there’s something coiled and secretive about Hawley that colors his daughter’s sense of the world. (His massive collection of guns suggests that he’s always bracing for something ghastly.) In every home they’ve ever had — and they’ve had many — Hawley immortalizes his late wife with a makeshift shrine of photos and knickknacks in the bathroom. But who was this lost woman, really? As much as Loo idealizes her father, she lives in a constant state of thirst for scraps of information about her mother.

Lovely, richly written but hardly electrifying — so what accounts for this novel’s explosive momentum?

For that, Tinti leads us repeatedly to the surface of Hawley’s taut body. There, etched in scar tissue, are the tales of 12 bullets. Every other chapter of the novel takes us back to some near-deadly adventure in Hawley’s criminal past that started with robbing gas stations and ended with fencing priceless antiques. We see foolhardy break-ins go bad, sure-thing robberies slip into carnage, simple money drops jerk out of control. “Bullets,” Hawley says through gritted teeth, “usually go right through me.” It’s a breathless relay race of missteps, disasters and murder that stretches for years.

It’s also a master class in literary suspense. Hercules himself might feel daunted by the labor of writing tales for 12 bullets, but Tinti is indefatigable. Each one of these stories drops us into a different setting somewhere in the country, establishes a tense situation in progress and then barrels along until slugs start tearing into flesh. Given the repetition, you would think we would come to anticipate Tinti’s methods and grow weary with these near-escapes, but each one is a heart-in-your-throat revelation, a thrilling mix of blood and love. Some of these well-drawn characters exist only for a few pages; others rear up again when you least expect them. And the ingenuity of these tales is matched by a rambunctious range of tones — from macabre comedy to scalding tragedy.

As the novel alternates between Hawley’s violent, itinerant past and his tranquil if lonely present, we come to understand the life that scarred him, shaped him and keeps him so anxious about his daughter’s safety. “The past never leaves you,” Hawley tells Loo. “It’s like a shadow, always trying to catch up.” That’s a mystery that Loo solves along with us until, inevitably, her father’s history and her own life converge.

This would all be empty calories if Tinti weren’t also such a gorgeous writer, if she didn’t have such a profound sense of the complex affections between a man wrecked by sorrow and the daughter he hoped “would not end up like him.” She does end up like him, of course, but only in the best way. She grasps the dimensions of her father’s criminal past while gaining an appreciation for his heroic nature. And in the process, she understands something essential about everyone. “Their hearts were all cycling through the same madness,” she thinks, “the discovery, the bliss, the loss, the despair — like planets taking turns in orbit around the sun.”

Ron Charles is the editor of Book World. You can follow him @RonCharles.

On April 7 at 7 p.m., Hannah Tinti will be at Politics and Prose, 5015 Connecticut Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20008.

Oprah Magazine Review

Newsday ★ Review

‘The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley’ review:

Hannah Tinti novel finds humanity in criminal father

March 24, 2017 By Dan Cryer Special to Newsday

Hannah Tinti’s first novel was titled “The Good Thief.” It told the story of a 19th century orphan caught up, against his will, with a ragtag band of con men and grave robbers. Her second, “The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley,” depicts a thief in our time who may have goodness in him, but it’s often hard to see.

The novel’s opening line — “When Loo was twelve years old her father taught her how to shoot a gun” — hints at the morally ambiguous territory readers are about to enter. Not that gun ownership is a bad thing, but we quickly learn that Loo’s father, Samuel Hawley, has many guns and has not hesitated to aim them at people. He is a man with many secrets, a man on the run.

Loo (short for Louise) has never known her mother, who died during her infancy. She has spent her young life moving from place to place while her father worked at odd jobs. Now that she’s about to enter her teens, they’ve settled down in her mother’s hometown, the fictional Olympus, Massachusetts, a seaside town of fishermen and waitresses.

Until now, it’s always been just father and daughter, alone in the world. But living in a community reveals Loo’s hot temper and tendency to get into fights. Her brawny father not only earns local celebrity by winning an annual greasy pole competition but arouses suspicion because of all the bullet-wound scars exposed by his shirtless heroics.

In interviews, Tinti has remarked that her novel was inspired by the mythical 12 labors of Hercules, a son of Zeus who killed his wife and children after going insane. To atone for his crimes, he was ordered to perform extraordinary feats of strength against a series of fantastical beasts scattered across the ancient world.

Hawley, too, is a wounded soul, and each of his wounds has a story to tell. His dangerous labors, his “jobs,” are undertaken at the behest of criminals. So, like Hercules, he wanders across the American map from Arizona to Alaska to Wisconsin and so on. The book’s narrative jumps back and forth between these violent scenes and Olympus, where conflict is more prosaic, if still troubling.

Tinti makes each of her crime scenes wildly different yet equally suspenseful. As skillful as she is, she never romanticizes her bad actors. What most deeply interests her is the stumbling, fumbling humanity that results in bad actions.

Hawley is one of those men who can’t fathom how he’s sabotaged his own hopes for a better life. Despite his best intentions — for his wife and daughter — his foolish choices keep tripping him up. “The past is like a shadow,” he laments, always trying to catch up.”

Some observers might brand him a loser. Tinti doesn’t. Like Russell Banks or Richard Russo, she urges us to be open to the humanity beneath the screw-up, the kernel of goodness beneath the lawbreaker. Her ordinary people just want to be loved. A woman who begs Hawley not to kill her husband says, “I’m the only one who knows him.” Of the father who abandoned his family, Loo’s boyfriend grieves, “I don’t think he wanted a family.”

Those yearnings aren’t that different from Loo’s own. Perplexed by the everyday confusions of adolescence, Loo is nonetheless determined to discover the truth about her mother’s death and her father’s past. Along the way, she finds surprising strengths within. Tinti’s own considerable strengths make us care about the outcome. She fuses urgent, vibrant storytelling with a keen understanding of broken people desperate to be whole.

New Yorker Review

Bookpage Review

THE TWELVE LIVES OF SAMUEL HAWLEY

by Hannah Tinti

Dial

$27, 400 pages

ISBN: 9780812989885

Audio, ebook available

Who has more lives than a cat and the bullet scars to prove it? That would be Samuel Hawley, the fascinatingly complicated and morally dubious titular character of Hannah Tinti’s gorgeous and gut-wrenching new novel, The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley. Having escaped more than his fair share of criminal capers by little more than the skin of his teeth, Hawley has spent most of his life on the lam, pulling up stakes and starting over with his daughter, Loo, whenever a job goes poorly. But when Loo turns 12, Hawley decides a little stability might serve her well and moves them to Olympus, Massachusetts, the small coastal village where Loo’s dead mother spent her girlhood. As the two perennial outsiders cautiously become part of a community, the past that Hawley has spent so long running from begins to close in on them. Loo’s adolescent misadventures are interspersed with histories of the dozen bullet wounds that decorate Hawley’s body, the narrative nimbly flitting between past and present day until the two timelines merge in a deadly and devastating climax. Cinematic in its scope, this expansive novel confidently dwells in the murky liminal spaces of human morality while exploring enduring topics of time, death, love and grief. Tinti has creating a darkly daring (yet oddly uplifting) book that severs as a beguiling study in contrasts and contradictions, one that will leave readers pondering the conundrum of whether her protagonist is a good man who had done bad things or a bad man who has done good things. Expertly infusing old-fashioned storytelling with a modern sensibility, Tinti blends spaghetti Western, literary suspense and mythology to great success. –Stephenie Harrison

Booklist ★ Review

★THE TWELVE LIVES OF SAMUEL HAWLEY

Tinti, Hannah (author)

Mar. 2017. 400p. Dial, hardcover, $27 (9780812989885).

REVIEW. First published January 1, 2017 (Booklist).

Tinti follows her acclaimed first novel, The Good Thief (2008), with another atmospheric, complexly suspenseful saga centered on an imperiled child under the care and tutelage of an outlaw. Sam Hawley’s sole reason for living after the drowning death of his wife, Lily, is his daughter. As for Loo, she is mostly content living on the run with her father, driving cross-country in a truck full of guns and staying in shabby motels in which Sam carefully sets up a bathroom shrine to Lily comprising photographs and her makeup, shampoo, and robe. But as Loo nears 12, Sam decides she needs a more stable life and risks settling down in the coastal Massachusetts town where Lily grew up and where Lily’s angry mother, Mabel, still lives, certain that Sam is responsible for her daughter’s demise. As Loo and Sam take measure of the troubles at hand, Tinti turns back the wheel of time and tells the hair-raising stories of each of the 12 bullet wounds scarring Sam’s battle-ready body. In between these wild flashbacks, Loo comes of age and embarks on her own dangerous escapades. With life-or-death struggles in dramatic settings, including a calving glacier, and starring a fiercely loving, reluctant criminal and a girl of grit and wonder, Tinti has forged a breathtaking novel of violence and tenderness. — Donna Seaman