A Heroine Comes of Age With Her Pistol-Packing Father

Review by Pete Hamill

New York Times, April 11, 2017

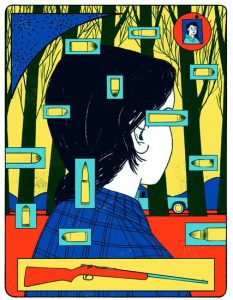

The engine powering Hannah Tinti’s complex new novel, “The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley,” is presented in the very first sentence: “When Loo was 12 years old her father taught her how to shoot a gun.” Bang, bang. Guns are normal in the Hawley household, where Loo (short for Louise) and her father, Samuel, live together. He keeps an assortment of firearms in his room, in closets, in boxes and in duffel bags. He often cleans them at the kitchen table, with the caressing attention of a priest. His daughter is not allowed to touch them. But they are there, and she watches intensely to learn “what she could about their secrets.”

Christina Daura

He leads her into the nearby woods with her grandfather’s rifle hanging across his shoulders. He is in his 40s now, tall and lean, looking younger than his age. When they are alone in a clearing, he gives her a first lesson in shooting. The target is a tree in the woods. Hawley talks her through the moves, including the release of a half-breath just before shooting. She sets herself, aims, then pulls the trigger.

And misses.

“Everyone misses,” Hawley tells her, scratching his nose. “Your mother missed.”

“She did?”

“The first time,” he says. “Now slide the bolt.”

Loo’s mother, Lily, died accidentally in a lake in distant Wisconsin before the young Loo could truly remember her. That loss provides an emotional anchor for Tinti’s story — and also for Loo herself, who still disappears at least once a day into the bathroom where Hawley has created an improvised shrine to his dead wife. As father and daughter moved around the unfamiliar American countryside, often abruptly, he always took the elements of the shrine with him to the next place. Photographs, a grocery list, the scrawled remnants of a dream. Like visible fragments of memory. The shrine and the guns establish a sense of home, a sense of continuity as Loo grows up. She may not recover her mother, but eventually she will master the holy art of shooting.

The story is bound together by memory as a kind of highlight film. Which is to say, by memory as it actually is and not as a neat, banal narrative or a huge baroque melodrama. Loo’s memories, and her father’s, are often triggered by subtle moments: a snatch of song, the rumble of fireworks, the aroma of food, sudden ripples of offstage laughter. And yes, pictures in a cramped bathroom. Sometimes the sun gleams in those images. But more often they are streaked by deep, threatening shadows. In this portrait, those shadows also obscure the true nature of Samuel Hawley.

The reason: Hawley is an outlaw. Not a gangster, because he retains no membership in a gang. Hawley is a freelancer, using his skill with guns to enforce criminal assignments: picking up certain very valuable cargo, usually in states where he does not live, and delivering it for a fee to the master planners. He steals cars to get around. He does what is necessary to survive his assignment. Hurting strangers. Killing, if that is necessary. He has a few freelance criminal friends, loners shaped by jails and violence. They often work together. In civilian life, Hawley poses as a fisherman or a house painter. He carefully hides his true identity from his daughter.

But he also pays a price. The 12 lives of the novel’s title are represented by 12 bullet wounds in his body, a kind of stations-of-the-cross marker for the scars Hawley has suffered in the living of his shadow life. His body has been punctured by too many bullets, along with the interior wound of losing his wife, and his great fear of harm coming to his daughter. Hawley’s love for Loo is tender and pure, a reprieve from an otherwise sinful existence. It makes Hawley an admirable father, and the novel more than a case for the humanity of gun nuts.

As his own story moves on, Hawley begins to self-medicate against physical pain or mental agony. He teaches his daughter to roll cigarettes for him. And he chooses alcohol as his own most useful medicine. The alcoholic blur pushes away the sharp edges in his mind. It doesn’t matter where father and daughter are. San Francisco. Oklahoma. Massachusetts. What matters is to sleep at night. And for Loo to go to a regular school and make friends. And so they do, in Olympus as in their other homes. But when Hawley digs for clams at the shore, he always has his back to the sea while he watches the people.

The story has a few other important characters. One is Loo’s maternal grandmother, Mabel Ridge, who is severe and wintry, as if convinced that Hawley and Loo are responsible for Lily’s death. There’s an insecure boy named Marshall Hicks, who once got fresh with Loo. Her response: She broke one of his fingers. Later, they fall in love. When Hawley is away, Marshall comes to sleep with Loo. Now they are seeing each other more clearly, as evoked by Tinti’s keen eye:

“Marshall sat up and looked around Loo’s room, his eyes resting on each piece of furniture and item on her bureau. A bowl of shells, a strip of Skee-Ball tickets from the county fair, a pile of comic books, novels and astronomy guides, some half-melted candles from a power outage, a wad of balled-up tissues from her last cold, a small batch of cormorant feathers that she’d found and kept, because she liked their iridescent black color. Loo watched him puzzle over each object. It was as if he was measuring her life.”

There are surprises too. And diversions. And mysteries. There is an extended scene with Hawley’s long absent father, who vanishes again when it ends: A vision? A delusion? We don’t know, but we read on, carried by Tinti’s seductive prose. She has a deep feeling for the passage of time and its effect on character. And when it’s appropriate, she can use her vivid language to express the ripping depth of human pain.

As this strikingly symphonic novel enters its last movement, the final bars remind us that of all the painful wounds that humans can endure, the worst are self-inflicted. The evidence is there in the scar tissue that pebbles the body of Samuel Hawley, and there too in the less visible scars on his heart.

Pete Hamill has written for New York newspapers and magazines since 1960 and has published 22 books, including the novels “Snow in August” and “Forever.” He is a writer in residence at the Carter Journalism Institute at New York University.