Hannah Tinti on T.S. Eliot in

The Atlantic

When Writing Is Actually About Waiting

The Atlantic

By Joe Fassler

In this episode, Hannah Tinti, the author of The Good Thief, explains what she learned about patience and risk from the T.S. Eliot poem “East Coker.”

________________________________________

Two hundred and fifty pages in, Hannah Tinti finally admitted things weren’t working out with her book. It was supposed to be the follow-up to her acclaimed first novel, The Good Thief, and the manuscript was competent—but didn’t have the most important thing, the ineffable quality that brings a story to life. Then she discovered lines from T. S. Eliot’s “East Coker” that gave her the courage to toss the whole thing out and start again, and changed her writing process for good.

“East Coker,” which Eliot started writing in 1939 after a four-year drought, is a prayer for creative release: for the ability to remain patient, to find peace inside of doubt, to hear music in the quiet. In a conversation for this series, Tinti explained how the poem taught her to push the outside world away and write for the right reasons—without hope for success or fear of failure—and why she’ll forever keep these lines taped above her desk.

Now, almost nine years after The Good Thief was published, Tinti’s second novel has arrived. The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley reimagines the title character’s criminal career as a series of Herculean labors, and his body bears the signs: A dozen pinkish bullet scars pucker his skin, each one from a job gone wrong. The novel begins with Hawley in semi-retirement, traveling with his young daughter, Loo, whose growing fascination with violence is only matched by her curiosity about her mother’s mysterious death. As the story of each bullet wound is revealed in a series of interspersed flashbacks, and as Loo starts to uncover the past Hawley’s running from, the picture darkens, and deepens.

Hannah Tinti’s story collection Animal Crackers was shortlisted for the PEN/Hemingway Prize; The Good Thief won the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. She’s also the co-founder and executive editor of One Story, an award-winning magazine that publishes just a single story per issue, and literary commentator for NPR’s Selected Shorts. She spoke to me by phone.

________________________________________

Hannah Tinti: A friend of mine, the writer Mari L’Esperance, used to email a group of us periodically with the text of a poem. It was just a private thing for friends, but I loved it—especially because my background is in fiction, so I was often being introduced to texts I hadn’t read before. One day Mari sent a poem that brought me to tears: an excerpt from “East Coker,” part of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets.

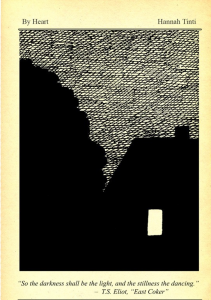

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love,

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

When a piece of writing strikes me, I’ll print it out and tape it into my journal. This poem I printed out twice: once for my notebook and another copy that I put up right above my desk. At the time, I was going through my own darkness, and it moved me profoundly, this idea of finding a way to wait. I read this poem over and over, each time I looked up from my desk, and learned to be content inside the struggle—understanding that there would be an end to my sadness, even if there was no way for me to know when that end would come. You can find peace within that. In the waiting.

When I first read this poem, I had aspirations of a certain kind of life—personally and professionally—that seemed to hinge on specific goals. If I can just finish this draft. If I can just sell this book. If I can just, if I can just. You think these landmarks are going to solve your problems, or give you some sort of deeper solace. But they don’t. That’s why it’s better to wait without hope. At least, that’s my reading of the line. To let go of the dream that something or someone will come along and magically solve everything. That’s a form of vanity, or a form of fear. It’s the wrong thing to hope for.

I taped these lines over my writing desk because they’re also a powerful reminder about staying in the moment, deep inside the work, without worrying about some future result. That became very important with my new novel, The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley, which began with a false start.Hitting bottom gave me the courage to chuck everything I’d written and start from scratch.

After the publication of my last book, The Good Thief, I felt a lot of pressure to begin a new project. I work full-time, but at night and on the weekends I was putting in the hours, sitting at the desk, trying to get the word count in each day. Two years in, I had a few hundred pages but they were full of anxiety. Full of the fear of failure. Full of other people’s expectations. I was trying to write because I felt like I should be writing. But there was no life in those words.

At the same time, the rest of my life wasn’t going so great either. I went through a bad breakup. I was financially unstable. And several members of my family were diagnosed with cancer at the same time. I was spending a lot of time in hospitals, trying to help the people I love go through operations and treatments. It was a tough time.

The breaking point came when I was pretty emotionally low, and decided to rent a cabin on Whidbey Island, which is a place I’d been before that had really helped my writing. I flew across the country and rented a car. Put it all on credit cards. And three blocks from the rental place, I got in a terrible accident: A woman ran through a red light and destroyed the car I was driving. I hadn’t taken the insurance, so that was another $15,000. The police had to pry the doors open with a crowbar. And I just felt, “Dear God, what else could happen? What else could go wrong?”

At the same time, once I sat on the sidewalk, and brushed the broken glass from my hair, I was grateful, deeply grateful, to still be alive. Who knows how much time any of us has? This was on my mind already, as I was worried about losing my family. They were fighting for each new day. In comparison, this accident was nothing. I got to my feet and limped back to the rental car place. I got a second car and continued on.

Somehow, hitting bottom gave me the courage to chuck everything I’d written and start from scratch. But it took getting to a place where I had nothing to lose to write what I wanted to write, simply because I wanted to write it. I wrote with the idea that nobody was going to see the words. Without hope of any kind. And those pages turned into the first chapters of my new novel, The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley. Through it all, T.S. Eliot gave me much solace.

The day-to-day writing was still a slog. It’s always a slog. But letting go of expectations enabled me to be much more creative. It’s like the first line of the excerpt: I said to my soul, be still. I dove into a new world and tried to be present for the characters, to just show up for the story I was trying to tell. This allowed me to take risks, too. Because if you’re waiting without hope, if you’re waiting without love, waiting without waiting for the wrong thing, you start to feel brave enough to say, “What the hell? I might as well try this.”

Another thing that helped was that I started to draw. I’d gone to a lecture that Lynda Barry gave about creativity and the human mind, and she spoke about how by doodling or doing little sketches, you can get your brain into a more imaginative space. That was a part of my process, as well, and another kind of creative freedom—the drawings were another thing nobody was going to see. They didn’t add to my word count. But they helped to quiet my mind. That kind of stillness is necessary, if you’re going to try and peel back some of the layers of what it means to be alive.

I don’t write every day. It ebbs and flows. But when I have a project that I’m working intently on, I tend to write at night. I think it gets back to that same word: stillness. The world starts to fall asleep. The emails stop coming in. The phone and texts go quiet. Even social media slows down. It’s almost like there’s more energy in the air for me to access. From 11 p.m. until 2 or 3 in the morning, that’s when I write my best stuff. You feel like you’re doing it in secret. That nobody is watching. All around you, people are dreaming. You can almost get yourself into a dream-like state. That’s much harder to do in the middle of the day.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought. For me, that line means accepting that you don’t know the whole story yet, both in your life, and with whatever you’re trying to write. It requires trusting that things are going to make sense eventually, even if you can’t make sense of them now. When I try to force things, get too technical or overthink the plot, the story loses energy. Things go better when I work instinctually and trust my subconscious. As I’ve gotten older, it’s become easier to do this. Because I know it’s worked before.

For example, at one point, when I was writing The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley, a whale showed up in a scene. At first I thought, “Dear God, who the hell do you think you are? You’re not a good enough writer to have a whale in your book.” It’s not only because of the giant, looming shadow of Melville—there’s a cheesiness to whales, too, that can easily feel overdone. But when you’re a writer waiting without hope, it doesn’t matter. I told myself that no one was ever going to read about my lame-ass whale. So why not leave it in the book, and instead challenge myself to try and make it work? I’m so glad that I didn’t follow my fears and cut that humpback, because it ended up being a really important part of the story, and wove together many elements about the nature of life and death that I was trying to explore.

It can be hard to learn to tolerate risk that way. But you need to open those doors and take those chances. As an editor, I see a lot of work that’s very polished, but just doesn’t have that spark of life. The writing might be beautiful, but it doesn’t provoke emotion—which is something I’m always looking for. To feel my throat get tight, or be so engrossed that I miss my subway stop. I want to be transported. And often that experience comes from work that’s a little more raw. Maybe the story has some structural problems. Maybe their grammar is messy, or their ending or beginning is weak. As an editor, those are things I can fix. But I cannot inject fire into something when it’s not there.

Writing that way, finding that spark, requires being still in the suffering. Trusting that a reason will reveal itself in the future. Letting go of trying to resolve or understand and just keep going. Keep working. Wait in the unknowingness. That’s what I’m trying to do, anyway. I struggle every day, but when I look up from my desk, Eliot’s words are a comfort. That darkness will bring the light. That one day stillness will feel like dancing.