A thriller with heart:

Hannah Tinti’s ‘The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley’

by Ron Charles

If only I’d had a copy of Hannah Tinti’s terrific new novel, “The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley.” This is the ancient myth of Hercules — the plot of all plots — re-engineered into a modern-day wonder. Tinti, the editor and co-founder of One Story magazine, knows how to cast the old campfire spell. I was so desperate to find out what happened to these characters that I had to keep bargaining with myself to stop from jumping ahead to the end. (Matt Reeves, lined up to direct the next Batman movie, has already optioned the novel for television.)

The story unfolds in Olympus, but not the celestial realm of Zeus and his family. This is Olympus, Mass., a small fishing town, which is typical of the radical transformations Tinti makes to her source material. Having grown up in Salem, she understands the flinty personalities of New England, that baffling tension between self-reliance and community spirit.

Samuel Hawley is a widower who has just moved into town with his 12-year-old daughter, Loo. He’s ruggedly handsome enough to turn heads but gruff enough to keep people at a distance — a conflicted, compromised hero whose lineage stretches all the way from the Old West to the old gods. Loo, meanwhile, is a precocious girl who “had grown strange,” Tinti writes, “the way children will when set apart.” Although Olympus is where Loo’s late mother once lived, the town regards these new neighbors with suspicion. Loo is cruelly teased at school until she beats a few of her tormentors to a bloody pulp. Her father objects only because she got caught.

On one level, this is the tender story of a girl trying to carve out a usable identity for herself while maturing in the shade of her father’s endless grief. Loving as he is, devoted as he is, there’s something coiled and secretive about Hawley that colors his daughter’s sense of the world. (His massive collection of guns suggests that he’s always bracing for something ghastly.) In every home they’ve ever had — and they’ve had many — Hawley immortalizes his late wife with a makeshift shrine of photos and knickknacks in the bathroom. But who was this lost woman, really? As much as Loo idealizes her father, she lives in a constant state of thirst for scraps of information about her mother.

Lovely, richly written but hardly electrifying — so what accounts for this novel’s explosive momentum?

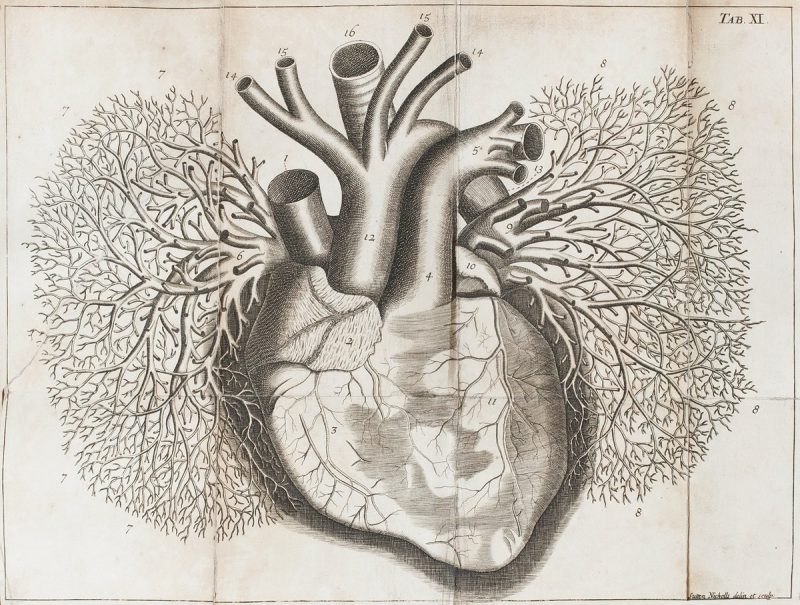

For that, Tinti leads us repeatedly to the surface of Hawley’s taut body. There, etched in scar tissue, are the tales of 12 bullets. Every other chapter of the novel takes us back to some near-deadly adventure in Hawley’s criminal past that started with robbing gas stations and ended with fencing priceless antiques. We see foolhardy break-ins go bad, sure-thing robberies slip into carnage, simple money drops jerk out of control. “Bullets,” Hawley says through gritted teeth, “usually go right through me.” It’s a breathless relay race of missteps, disasters and murder that stretches for years.

It’s also a master class in literary suspense. Hercules himself might feel daunted by the labor of writing tales for 12 bullets, but Tinti is indefatigable. Each one of these stories drops us into a different setting somewhere in the country, establishes a tense situation in progress and then barrels along until slugs start tearing into flesh. Given the repetition, you would think we would come to anticipate Tinti’s methods and grow weary with these near-escapes, but each one is a heart-in-your-throat revelation, a thrilling mix of blood and love. Some of these well-drawn characters exist only for a few pages; others rear up again when you least expect them. And the ingenuity of these tales is matched by a rambunctious range of tones — from macabre comedy to scalding tragedy.

As the novel alternates between Hawley’s violent, itinerant past and his tranquil if lonely present, we come to understand the life that scarred him, shaped him and keeps him so anxious about his daughter’s safety. “The past never leaves you,” Hawley tells Loo. “It’s like a shadow, always trying to catch up.” That’s a mystery that Loo solves along with us until, inevitably, her father’s history and her own life converge.

This would all be empty calories if Tinti weren’t also such a gorgeous writer, if she didn’t have such a profound sense of the complex affections between a man wrecked by sorrow and the daughter he hoped “would not end up like him.” She does end up like him, of course, but only in the best way. She grasps the dimensions of her father’s criminal past while gaining an appreciation for his heroic nature. And in the process, she understands something essential about everyone. “Their hearts were all cycling through the same madness,” she thinks, “the discovery, the bliss, the loss, the despair — like planets taking turns in orbit around the sun.”

Ron Charles is the editor of Book World. You can follow him @RonCharles.

On April 7 at 7 p.m., Hannah Tinti will be at Politics and Prose, 5015 Connecticut Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20008.